SNR (2024-Ongoing)

To the immediate west of DC, in the dense hills of West Virginia’s panhandle, lies the National Radio Quiet Zone: a 13,000 square foot area telecommunication dark zone. The area was designated as such to clarify transmissions for two highly sensitive radio telescopes, owned by the NSF and Navy, nestled in the heart of Pocahontas County.

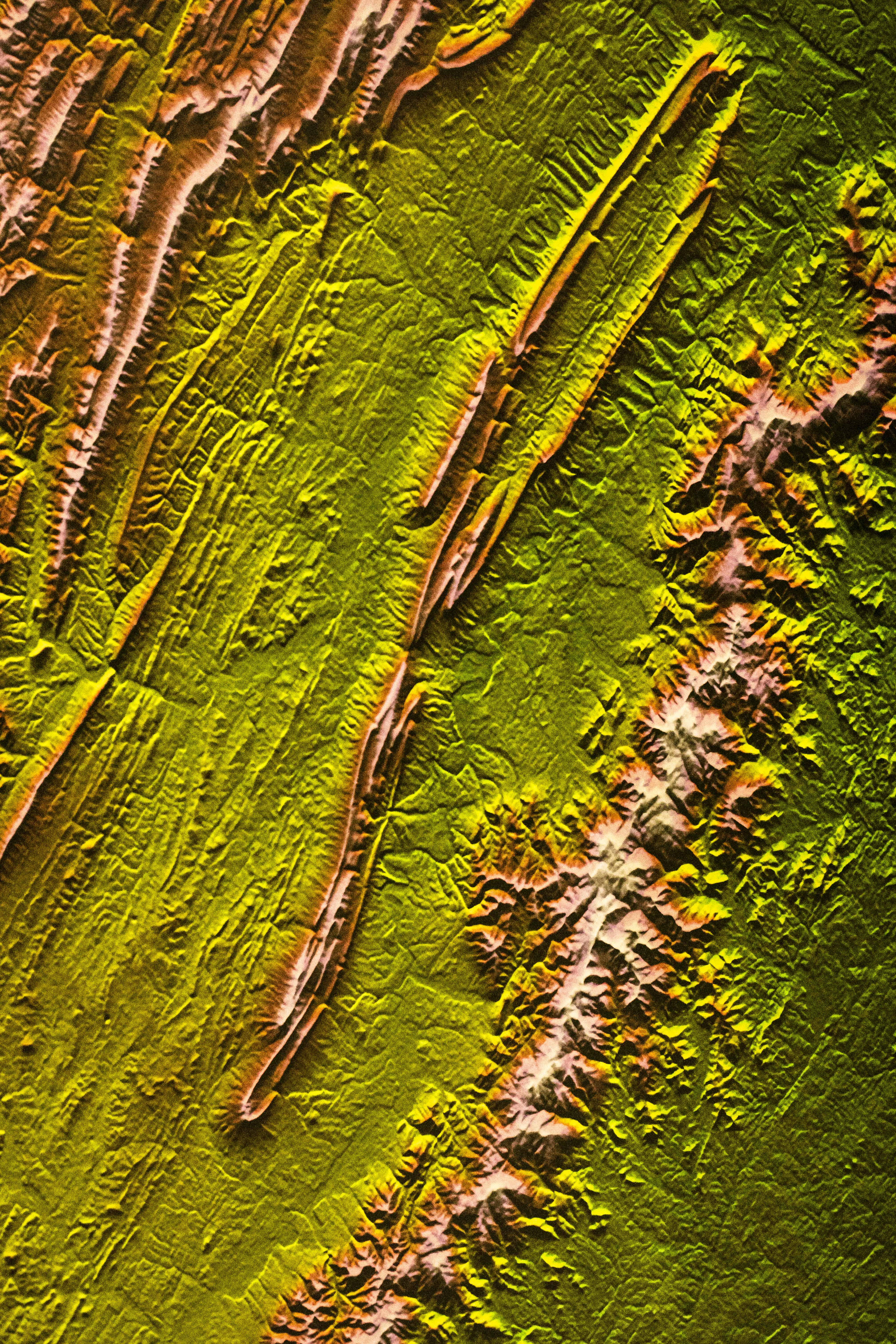

West Virginia’s relationship with ‘Dark Zones’ - and their mapping and subsequent extraction- is extensive, from its beginnings on the unmapped colonial frontier, to its mining industry which continues into the present, seeking new sources of power underground. From the solitude of the NRQZ, various scientific and political operations aim to probe and penetrate space above and below. The massive radio dishes in Green Bank and Sugar Grove aim to intercept all international wireless communications entering the country, locate abstract celestial bodies, and most notably attempt to communicate with intelligent life in space. Underground, sprawling cavern systems lie uncharted. The zone contains one of the densest concentrations of caves on the planet, which are continually being discovered and mapped at a rapid pace.

What I am particularly interested in with respect to the NRQZ is its status as a ‘last frontier’. West Virginia is no longer a ‘frontier’ in the sense of it being unsettled lateral territory. Yet, it is a frontier in the sense of it being an observatory: a vantage point for viewing more abstract, uninhabitable realms, a place of yearning and dreaming. It is, of course a means of satisfying (pacifying?) American colonialist desires, but beyond that, I think there is also an element here of appealing to the divine, the sublime. To go underground, or to probe space, this is not something the naked eye is capable of doing. Specialist equipment is necessary to ‘cut’ through the dark and reveal its contents, akin to another mining operation. But what’s being extracted here? Despite needing electronic technology to see past certain points, to actually access viewing also requires a bit of nakedness before these spaces. You have to cut yourself off from the existing world outside of the zone to truly see inside of it. (My first visit to the green bank telescope, I could not photograph it, as there is no electronics whatsoever allowed in its vicinity outside of analog film cameras. It is a true ritual object, something you come before as your bare self.)

People flock to the NRQZ because of a very specific kind of quiet, a quiet that provides clarity and the ability to cut through noise. I began visiting the area with my local caving club in pursuit of that quiet. It is a frontier of the sublime. My aim in making a body of work in/under/about the zone is not meant to be merely analytical, but initiatory. The approach is a kind of split between above/below: documentary coverage of surveying projects in various cave systems (emphasis on figure study; the headlamp beam and contorted, crawling body as a visual device), and of the telescopes/sky/those who live around them.

West Virginia’s relationship with ‘Dark Zones’ - and their mapping and subsequent extraction- is extensive, from its beginnings on the unmapped colonial frontier, to its mining industry which continues into the present, seeking new sources of power underground. From the solitude of the NRQZ, various scientific and political operations aim to probe and penetrate space above and below. The massive radio dishes in Green Bank and Sugar Grove aim to intercept all international wireless communications entering the country, locate abstract celestial bodies, and most notably attempt to communicate with intelligent life in space. Underground, sprawling cavern systems lie uncharted. The zone contains one of the densest concentrations of caves on the planet, which are continually being discovered and mapped at a rapid pace.

What I am particularly interested in with respect to the NRQZ is its status as a ‘last frontier’. West Virginia is no longer a ‘frontier’ in the sense of it being unsettled lateral territory. Yet, it is a frontier in the sense of it being an observatory: a vantage point for viewing more abstract, uninhabitable realms, a place of yearning and dreaming. It is, of course a means of satisfying (pacifying?) American colonialist desires, but beyond that, I think there is also an element here of appealing to the divine, the sublime. To go underground, or to probe space, this is not something the naked eye is capable of doing. Specialist equipment is necessary to ‘cut’ through the dark and reveal its contents, akin to another mining operation. But what’s being extracted here? Despite needing electronic technology to see past certain points, to actually access viewing also requires a bit of nakedness before these spaces. You have to cut yourself off from the existing world outside of the zone to truly see inside of it. (My first visit to the green bank telescope, I could not photograph it, as there is no electronics whatsoever allowed in its vicinity outside of analog film cameras. It is a true ritual object, something you come before as your bare self.)

People flock to the NRQZ because of a very specific kind of quiet, a quiet that provides clarity and the ability to cut through noise. I began visiting the area with my local caving club in pursuit of that quiet. It is a frontier of the sublime. My aim in making a body of work in/under/about the zone is not meant to be merely analytical, but initiatory. The approach is a kind of split between above/below: documentary coverage of surveying projects in various cave systems (emphasis on figure study; the headlamp beam and contorted, crawling body as a visual device), and of the telescopes/sky/those who live around them.

HOME